motivational interviewing worksheets

What’s a structured intervention worksheet? What’s a Carey Guide? And what do judges and lawyers need to know about those things to interface with Probation effectively?

What’s a structured intervention worksheet? What’s a Carey Guide? And what do judges and lawyers need to know about those things to interface with Probation effectively?

Probation today doesn’t look like it did 20 years ago. Or even 5 years ago. Some of that evolution stems from Justice Reinvestment and other statutory changes. Things like CRV and quick dips didn’t even exist before 2011.

But much of the change is the result of a broader philosophical shift within community corrections, both in North Carolina and across the country. That shift is reflected in revised policies and training within the Division of Adult Correction. Probation would generally characterize its updated approach as “Evidence-Based Practices, ” or EBP. I wrote about those practices—focusing on the risk-needs assessment that Probation conducts on every supervised probationer during the first 60 days of supervision—in this post back in 2012. The general idea is to use the results of that assessment process to shape the probationer’s supervision in terms of how closely he or she will be watched, and how the officer will respond to noncompliance.

An important component of EBP in North Carolina is probation officers’ use of structured worksheets to guide their interactions with probationers. Some of the worksheets they use were developed in-house, while others are “name brand.” In the latter category, the name you’re most likely to hear is “Carey Guides, ” a handbook series published by Carey Group Publishing.

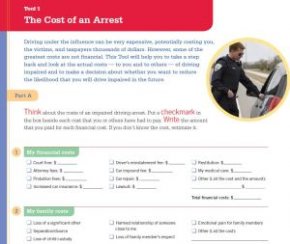

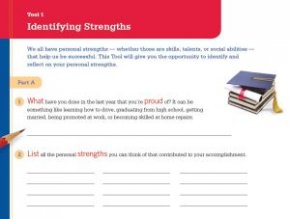

There are many titles in the Carey Guide series, some focused on particular crimes (impaired driving, for example) and others focused on particular offender needs (like anger issues, empathy, or family challenges). To give you a sense of their contents, the Impaired Driving guide includes a page that walks through the many costs—financial, familial, emotional—associated with a DWI arrest (something Shea blogged about here). Another guide called Maximizing Strengths helps officers draw out the good and positive things in a probationer’s life, so they can supervise the offender in a way that plays to his or her strengths. Those of you who work in drug treatment court or other specialty courts may recognize in the guides elements of motivational interviewing and positive reinforcement that permeate those programs. It’s not rocket science, but the general idea is to promote a higher-level conversation between officer and offender that goes beyond the traditional emphasis on noncompliance and the threat of revocation.

There are many titles in the Carey Guide series, some focused on particular crimes (impaired driving, for example) and others focused on particular offender needs (like anger issues, empathy, or family challenges). To give you a sense of their contents, the Impaired Driving guide includes a page that walks through the many costs—financial, familial, emotional—associated with a DWI arrest (something Shea blogged about here). Another guide called Maximizing Strengths helps officers draw out the good and positive things in a probationer’s life, so they can supervise the offender in a way that plays to his or her strengths. Those of you who work in drug treatment court or other specialty courts may recognize in the guides elements of motivational interviewing and positive reinforcement that permeate those programs. It’s not rocket science, but the general idea is to promote a higher-level conversation between officer and offender that goes beyond the traditional emphasis on noncompliance and the threat of revocation.

Why am I writing about this? To be clear, it is not to endorse the general idea of using structured worksheets, and certainly not to endorse the Carey Group or any particular vendor that works in this area. Even though these supervision strategies largely happen behind the scenes from the court system’s perspective (there is no condition of probation that says “Do your Carey Guides”), I think there are a few reasons judges and lawyers should be generally aware of the structured worksheet phenomenon.

First, Probation is using them a lot. The graph below shows the increase in the use of structured worksheets since 2011

Probationers completed over 80, 000 structured worksheets last year. With that in mind, it is increasingly likely that an officer asked about a probationer’s progress will utter the words “Carey Guides” at some point. Knowing a little more about what those words mean might help a judge have a more informed conversation with the officer about the probationer, and possibly help tailor his or her response to a violation. More generally, I think you should have at least a passing familiarity with anything that’s happening that often.

Second, knowing more about the way Probation supervises offenders might steer you away from probation conditions that unintentionally operate as barriers to what they are trying to accomplish. A classic example is a condition requiring that a person be arrested on his or her first violation of a particular condition, like a positive drug screen (sometimes with the additional requirement of a particular bond—even though the court of appeals has said anticipatory bonds are to be avoided, State v. Hilbert, 145 N.C. App. 440 (2001)). I’m not here to stand in the way of what anybody thinks is necessary as a matter of public safety (assuming it is lawful), but I don’t mind passing along a message from Community Corrections that mandatory arrest conditions can impede their efforts to build rapport with probationers and supervise them in a more nuanced way, informed by the results of a risk-needs assessment that takes about two months to complete.